Japanese food has many specialised ingredients unique to the cuisine. Some ingredients are repeatedly used in my recipes. I thought it might be of help to you if I posted my Pantry Essentials for Japanese Home Cooking, explaining each item in detail with the brands I use and some photos.

If you have these in your cupboard, you’re well placed to cook delicious Japanese dishes. I tried to include all the items in the photo above plus some more in one post, but the post became too long. So today, I will post Part 1 of Pantry Essentials for Japanese Home Cooking. Part 2 will be posted next week.

The most fundamental Seasonings – SaShiSuSeSo

Apart from dashi stock, the most basic seasonings used in Japanese cooking are expressed as ‘SaShiSuSeSo’ (さしすせそ), which represents Satō (さとう, sugar), Shio (しお, salt), Su (す, vinegar), Syōyu/Seiu (しょうゆ/せいう, soy sauce), miso (みそ, miso). In old days, shyōyu was phonetically written as ‘せいう’ for the sound ‘shōyu’.

The sequence of these letters also represents the order in which you add them when cooking dishes. Sugar does not penetrate into the ingredients as fast as others, so you add sugar first. Soy sauce and miso are the last ingredients so that you won’t lose the flavour of these ingredients.

SaShiSuSeSo (さしすせそ) is also the alphabet order that the phonetic sounds of hiragana starting with ‘S’ are recited in. So this string of sounds forms a mnemonic for Japanese people when remembering these ingredients.

You might wonder why sake and mirin are not included in this list. They are classified as the seasonings that add a depth to the flavour. You will find more information about sake and mirin next week in Part 2 of my Pantry Essentials

Satō (砂糖, Sugar)

Just like in other countries, there are many varieties of sugar used in Japan. But I listed only a few that are often used in home-cooking.

Shirozatō (白砂糖, white sugar) – this is most commonly used in Japan and probably only in Japan. It is finer and moister than the white sugar we use in Australia.

Guranyūtō’ (グラニュー糖) – this is the sugar that is most commonly used around the world. We call it white sugar, but in Japan white sugar means shirozatō. The name ‘guranyūtō’ came from the word ‘granular’ because it is coarser than shirozatō.

Sanontō (三温糖, pronounce it as san-on-tō) – this is light brown sugar with a similar texture to shirozatō (see the photo below). It has a distinctive rich and sweet taste, therefore it is often used in simmering dishes. It is not the same as brown sugar.

Frrom left to right: A bag of shirozatō, Comparing shirozatō and sanontō, A bag of sanontō.

You can buy shirozatō and sanontō from Japanese grocery stores, but I use the Western-style white sugar instead.

Shio (塩, Salt)

The types of salt available and used in Japan are very similar to those in other countries. They include standard salt for cooking, sea salt, rock salt, and coarse salt, etc.

Salt is one of the Pantry Essentials for not only Japanese cuisine but all the cuisines in the world. So, I do not go in detail here.

A bag of Japanese sea salt – it says that the salt was sauced from Mexico or Australia, then diluted in the sea water of Japan.

Su (酢, Rice vinegar)

Japanese vinegar is noticeably more mellow than Western-style vinegars and has a distinct flavour. It is used in pickling, marinating, dressing, and sometimes in cooking. Just like Western-style vinegar, Japanese vinegar also has varieties.

Commonly used varieties are:

Komezu (米酢, rice vinegar) – made purely from rice. It is milder and does not have a sharp acidic smell. Perhaps because of this, sushi chefs use komezu to make sushi rice. You will see the kanji character ‘米酢’ on the label of the bottle to distinguish it from grain vinegar.

Zakkoku su (雑穀酢, grain vinegar) – made from a combination of wheat, rice, sake lees, and corn. Compared to rice vinegar, the acidity is sharper. It is cheaper than pure rice vinegar. The rice vinegar that you can buy from supermarkets often is grain vinegar.

Sushi su (寿司酢, vinegar for sushi rice) – this is a dressing made specifically for sushi rice. It consists of rice vinegar, sugar, and salt. Because it has a sweet flavour, it is suited to salad dressing too. You can make sushi su at home as you can see in my recipes Chirashi Sushi and Sushi Rolls, but it is handy to have a bottle of store-bought sushi su.

Kurozu (黒酢, black vinegar) – it is made from rice and rice kōji through a brewing process. The colour of kurozu is almost like whisky. It is available in a range of ages, just like whisky. The older it gets the thicker the vinegar becomes, and more expensive it gets – like this 10 years old Japanese kurozu. Chinese cuisine also uses a black vinegar, but the ingredients are different.

Kurozu however is usually consumed as a drink for good health, but you can use it in cooking to give more umami and richness to the dish.

From left to right: Mizkan brand komezu, Uchibori brand komezu, Obento brand zakkoku su, Mizkan zakkoku su.

Although it is generically called ‘rice vinegar’ and I use it in my recipes as a generic term, it refers to the first two varieties.

WHERE TO BUY AND WHERE TO STORE

You can buy grain vinegar from supermarkets as well as Japanese/Asian grocery stores. You may have to go to Japanese grocery stores and some Asian grocery stores to buy pure rice vinegar. I don’t use kurozu in my cooking.

I use Mizkan brand which sells both types of vinegar – grain vinegar and rice vinegar (my preference).

Storage: You can store rice vinegar at room temperature in a dark place.

Shyōyu (醤油, Soy sauce)

When you think of pantry essentials for Japanese cooking, I am sure you will think of soy sauce as one of the top 3 items.

Soy sauce is used as a seasoning and flavouring in cooking, as well as in dressings and for dipping. Japanese soy sauce is ‘sweeter’ and more delicate than Chinese soy sauce. The flavour is quite different too. So, unless specifically mentioned as an alternative, use Japanese soy sauce when cooking Japanese dishes.

Left: Usukuchi shōyu (light soy), Centre: Koikuchi shōyu (normal dark soy), Right: Gen-en shōyu (salt-reduced soy).

The main types of soy sauces are:

koikuchi shōyu (濃口醤油, dark soy sauce or just ‘soy sauce’) – the normal soy sauce widely used in general cooking as well as pouring over food.

Usukuchi shoyu (薄口醤油, light soy sauce) – lighter in colour and 10% saltier than normal soy sauce. Used in dishes to enhance the colour of the ingredients, or in noodle soups to make a light-coloured broth.

Gen-en shōyu (減塩醤油, salt-reduced soy sauce) – this is made using the same process as dark soy but the amount of salt is reduced to almost half. This was initially produced for people with hypertension, heart diseases, and kidney diseases but these days many people in Japan use this to reduce their salt intake.

Tamari shōyu (たまり醤油, tamari soy sauce) – this soy sauce is thicker and richer than normal soy sauce and used as dipping soy sauce for sashimi. It can also be used to make Teriyaki sauce.

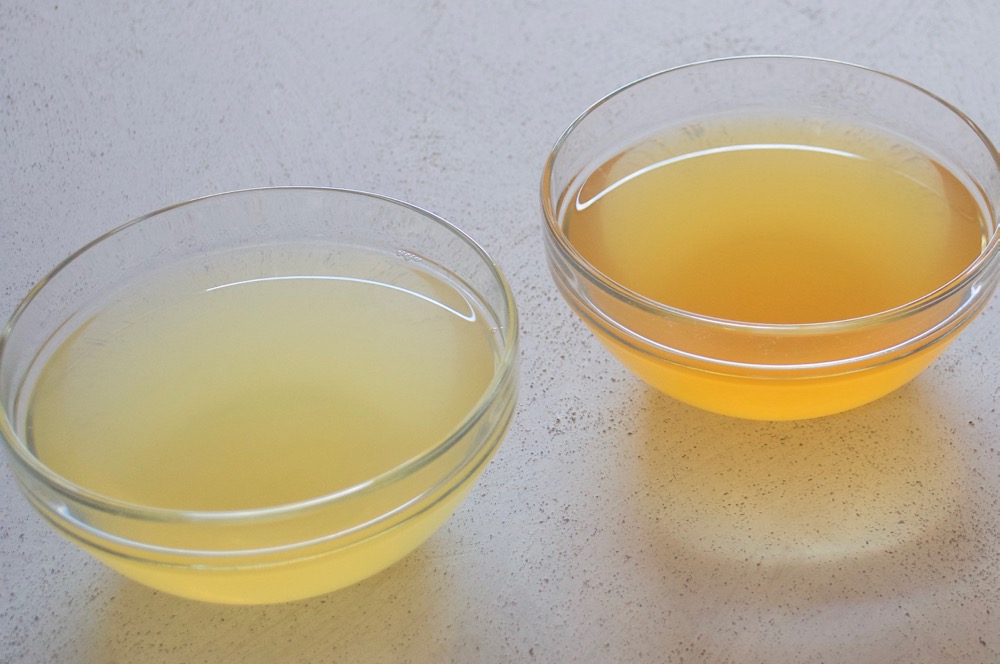

Shiro shōyu (白醤油, white soy sauce) – extremely light in colour, almost like the colour of fish sauce, as you can see in the photo below, comparing against usukuchi shyōyu. It contains a touch of sweetness but also a strong salty flavour. This is suitable for simmered dishes.

Left: shiro shyōyu, Right: usukuchi shyōyu.

Koikuchi shōyu is the most commonly used soy sauce at home. Unless specifically indicated, soy sauce means this type. You can get away with it for almost everything, even if the recipe might use usukuchi shōyu. The difference is that the colour of the broth becomes darker if you use normal soy sauce instead of usukuchi.

Where to Buy and where to store

Soy sauce is readily available at supermarkets and Japanese/Asian grocery stores. These days, you can even buy salt-reduced soy sauce at supermarkets. Kikkoman brand of koikuchi shōyu (photo below) appears to be the widely known brand and variety of the soy sauce.

I use either Kikkoman, Yamasa, or Higashimaru brand (whichever the cheapest at the time). You can buy these brands at Japanese/Asian grocery stores. Kikkoman is also available at supermarkets.

Storage: You can store soy sauce in a dark and cool place. But to be safe, store in the fridge after opening if you can.

Miso (味噌)

Perhaps another Japanese pantry essentials that you will think of straight away is miso. Miso is a salty, fermented soybean paste that’s packed with umami and rich flavour. It of course features in miso soup but is also widely used to flavour broths and stir fries, and for glazes like Dengaku. Marinades for meat, fish and vegetables is another way miso’s deeply savoury flavour is harnessed.

Although all miso has a brownish colour, the colour varies a lot depending on the region and the method of the miso production. In addition to soya beans, miso sometimes contains rice, barley, or other ingredients, and you can see grains in it.

Miso can be categorised by colour, ingredients, and taste.

Miso varieties by colour

Shiro miso (白味噌, white miso) – a light-coloured (almost beige colour) miso. It often contains less salt than other types of miso and you can even taste a sweetness. It is preferred by the people in the western part of Japan such as Kyoto and Osaka.

The most famous shiro miso is called Saikyo miso (西京味噌), meaning Kyoto-style miso. It is the sweetest miso in Japan, containing only about 4-5% salt.

Depending on the brand of shiro miso, the amount of salt included in the miso varies a lot. Shiro miso consumed in the eastern/northern part of Japan including Tokyo is not as sweet as the Western-style shiro miso. It can contain twice as much salt as Saikyo miso.

Aka miso (赤味噌, red miso) – has a deep reddish brown colour. It contains much more salt than sweet shiro miso, about 10-11%. Unlike shiro miso, which has a shorter fermentation period, aka miso takes more than a year to ferment, resulting in the dark colour. Aka miso has a rich flavour and people in the northern part of Japan tend to consume aka miso.

Tanshoku miso (淡色味噌, brown miso) – sits in the middle from both a colour and saltiness perspective. It usually contains about 10-12% salt. Most miso pastes you can buy at supermarkets outside Japan are tanshoku miso. This is the most commonly used miso in Japan as well, particularly in the eastern part of Japan.

Left: Shiro miso (white miso), Centre: Tanshoku miso (brown miso), Right: Aka miso (red miso).

Miso varieties by ingredient

Depending on the type of kōji (fermentation agent) used to make miso, miso can be classified into three varieties.

Kome miso (米味噌, rice miso) – made from soybeans, salt and rice kōji. The rice gives kome miso a hint of sweetness. These days, the majority of miso produced in Japan is kome miso. Shiro miso is a kind of kome miso.

Mugi miso (麦味噌, barley miso) -made from soybeans, salt, and barley kōji. Mugi miso has a rich barley flavour. It is produced mainly in the Kyūshū, Shikoku, and Chūgoku regions of Japan.

Mame miso (豆味噌, soybean miso) – made from just soybeans and salt. Mame miso is not as sweet as kome miso. Unlike other types of miso, mame miso does not lose the miso flavour easily after simmering for a while. This type of miso is produced manly in Nagoya district area.

Awase miso (合わせ味噌, blended miso) – Many of the brown miso varieties are awase miso, which is made from 2 or more kinds of miso ingredients. One of the very popular miso in Japan is awase miso.

Miso varieties by taste

Regardless of the colour or the ingredients of the miso, you can also distinguish miso by the sweetness and saltiness. The sweetness of the miso comes from the kōji and the saltiness comes from salt.

Ama miso (甘味噌, sweet miso) – this miso contains less salt and more kōji than others. The western region shiro miso, such as Saikyo miso, is ama miso. In Tokyo, there is a traditional red ama miso called Edo ama miso.

Amakuchi miso (甘口味噌, mild miso) – this miso has a moderate level of sweetness and saltiness. Most miso sold at shops and supermarkets is in this category. The sweetness and the saltiness can vary within this group.

Karakuchi miso (辛口味噌, salty miso) – this type of miso contains a higher level of salt and lower level of kōji, making the miso saltier than ama miso and amakuchi miso. The colour of the miso can be brownish to red.

Kōji Miso

You may also find a miso labelled ‘kōji miso’. It is almost like a product name. When particular attention is paid to kōji to make the miso tastier, they may call this particular miso ‘kōji miso’. It might be due to the higher ratio of kōji in miso, or the miso might contain kōji grain bits.

Kōji miso showing whitish koji grain bits.

From the categories explained above, you can now understand why so many varieties of miso are available on the market. It must confuse many people. But the above explanations hopefully give you a better understanding of miso. It is really up to your preference as to which colour and taste of miso you would like to use.

Important Note: The colour of the miso does not indicate the sweetness/saltiness of the miso. As you can see in the photo below, both miso packs are labelled as ‘shiro miso‘, but the left miso is the sweet shiro miso similar to Saikyo miso, which contains 2360 mg sodium per 100g miso. The right shiro miso is as salty as brown miso, containing 4800mg sodium. Check the nutrition label!

Some miso packs come with dashi stock already mixed in. Although it sounds convenient, the flavour of dashi is too light in my view.

Where to Buy and where to store

Varieties of miso are sold at supermarkets and Japanese/Asian grocery stores. You may have to go to Japanese grocery stores or Asian grocery stores to buy ama shiro miso (sweet white miso).

I always stock ama shiro miso (sweet white miso) and amakuchi awase miso (mild brown miso). I sometimes buy kōji miso and aka miso too.

Saikyo miso is the most famous brand of sweet white miso, which I always keep in the freezer (yes, Saikyo miso needs to be in the freezer). For awase miso, I buy Shinshūichi or Marukome brand, but I sometimes buy Hikari brand organic miso.

Storage: The quality of miso degrades when it is exposed to air. So, miso needs to be completely sealed and stored in the fridge. You can also freeze miso, which is a convenient way of storing it because miso does not become hard when frozen. Sweet white miso should be stored in the freezer once opened.

Dashi (出汁)

In addition to SaShiSuSeSo, I must include dashi in this post Pantry Essentials for Japanese Home Cooking – Part 1 even if dashi is not really a seasoning.

It is best to freshly make dashi when you need it. You can find variety of home-made dashi stock here. But there are dashi stock powders that you can buy from supermarkets and Japanese/Asian grocery stores. These are handy to have in your pantry.

Like stocks in Western food, it forms the foundation of countless Japanese dishes. There are quite a few different kinds of dashi, depending on the main ingredient used to get stock out of it.

Commonly used types of dashi are:

Katsuo dashi (鰹出汁) – made from katsuobushi (鰹節, dried bonito flakes) only. This is one of the most commonly used dashi stock due to its versatility. It is often used for miso soup and broth for udon/soba noodles.

Konbu dashi (昆布出汁) – made from konbu (昆布, dried kelp). It has a delicate flavour. It is suited for the dishes that make the best use of the original flavour of the ingredients, e.g. takikomi gohan (Japanese mixed rice) and simmered dishes.

Depending on where the kelp was harvested, the flavour of the konbu dashi differs. For vegetarians, konbu dashi is a good substitute for katsuo dashi, awase dashi and niboshi dashi.

Awase dashi (合わせ出汁) – made from katsuobushi (鰹節, dried bonito flakes) and konbu (dried kelp). Awase dashi is another commonly used dashi. It has a great degree of umami that comes from bonito flakes as well as konbu. It is best suited for simmering dishes and hot pot, but you can of course use it for miso soup too.

Niboshi dashi (煮干し出汁) – made from niboshi (煮干し, small dried sardines/anchovies). In Kansai region (the western part of Japan), niboshi is called ‘iriko’ (いりこ), and the dashi stock is called iriko dashi (いりこ出汁). Because of the fishy fragrance, it is often used for miso soup.

Shiitake dashi (椎茸出汁) – made from dried shiitake(椎茸) mushrooms by soaking them in water overnight. Shiitake dashi contains plenty of amino acid such as glutamic acid, which is one of the umami elements. It is often used in addition to katsuo dashi or awase dashi to add an extra flavour to the dashi stock.

Varieties of instant dashi (from left to right): Niboshi dashi powder, katsuo dashi powder, awase dashi pack, awase dashi pack with no salt.

Instant Dashi

Instant dashi is a convenient way of making dashi when you have no time. It comes in various forms for all the different types of dashi listed in the previous section.

There are two distinct forms of instant dashi.

Dashi packet – comes in a sachet containing finely shaved dashi ingredient(s). You place a pack in water and simmer to infuse umami from it. Because it contains only the ingredients that you will use if you were to make dashi from scratch, the dashi is very close to home-made dashi.

Dashi powder – comes either in very fine powder form or in granular form. Some dashi powders contain salt and food additives to achieve the good dashi flavour. Ajinomoto Hon-dashi is one of the widely used granular dashi. But it contains 1.2g of salt in 1 teaspoon of Hon-dashi powder. As a comparison, 1 teaspoon of soy sauce contains 0.9g of salt.

Left: granular form of instant dashi, Right: instant dashi packet.

It’s quite alright to use dashi powder but you need to be aware of what is included in the powder. This type of instant dashi is quite useful when you only need a very small amount of dashi to make a dipping sauce (such as Sesame Dipping Sauce for Steamed Chicken and Fish with Vegetables) and a dressing (as in Squid with Green Vinegar Dressing).

Where to Buy and where to store

You can buy instant dashi powder even at supermarkets. You may have to go to Japanese/Asian grocery stores to buy instant dashi packets.

I always keep a bagful of dashi packets and a few different flavours of dashi powder. Brand of instant dashi powder is not very important to me. I pay more attention to the kinds of dashi I need and avoid instant dashi pack/powder that contain salt if possible.

Storage: Dashi (liquid, not powder) can be stored in the fridge for 2-3 days. You can also freeze dashi for 3 weeks. When freezing dashi, you may want to make some small cubes of frozen dashi as well. They become handy when you only need a small amount of dashi to make a sauce or dressing. Dashi packet or powder can be stored in the pantry.

I know the items listed in Pantry Essentials for Japanese Home Cooking – Part 1 is nowhere near the complete list of groceries. I am hoping that combined with Pantry Essentials for Japanese Home Cooking – Part 2, which I will post next week, you will know a bit better about key ingredients for Japanese cooking.

Yumiko![]()

Many thanks Yumiko,

This is an excellent, useful resource for anyone wishing to cook authentic Japanese food, looking forward to part two next week.

Take care,

Michelle

Hi Michelle, thanks! I am typing up Part 2 as I speak!

I agree with the previous comment. You have answered many questions and the work that you have put into the post is wonderful. Thank you!

Hi Catherine, you are most welcome! I’m glad to know that some questions people had were answered.

This is a great intro to setting up a Japanese pantry for someone who’s not Japanese but loves cooking Japanese food, thank you so much! 🙂

Hi Steffi, glad to know that the post is useful.

This list was absolutely wonderful. Thank you so much for all the explanations along with the products.

Hi Brit, you are welcome!

Hi Yumiko! This is so interesting and so helpful! I especially appreciate your explanations about why certain ingredients are added in a particular order. Can’t wait for part 2!

Hi Bebe, it’s so easy to remember the basic seasonings and orders, right?

Thank You for the Excellent Over-view. Best I’ve ever seen.

Hi Greg, thanks!

Thank you, Yumiko! This post answers so many questions for me! I really appreciate the work you (obviously) put into this!

Hi Dianne, it’s my pleasure. I must admit, it took much longer than the usual recipe post.

Thank you for this post, it’s excellent and so helpful. I’m a new subscriber to your site and I’m loving the recipes.

Hi KAren, welcome to RTJ. Such a good timing to post this for you!

Hello Yumiko, thank you for such detailed information and accompanying photos. I really appreciate the effort you have put in. This is extremely helpful!! 🙂

Hi Sarah, thanks! I hope Part 2 is as useful as Part 1.

Thank you, Nagi! I recently purchased some miso to make Miso Glazed Salmon (which was delicious). I’m glad to read that you can freeze it because I spooned the rest of the miso into ice cube tray sections for future ready-to-use measurements.

Hi Laurie, you are welcome.